Bill Gammage, in his brilliant book The Biggest Estate on Earth describes fire as ‘drought with legs’. He also explains how ‘eucalypts and fire formed an alliance, which people joined’.

Australians living in almost the entire continent are familiar with fire as an agent for cleansing and renewal: keeping the scrub down, promoting seed creation and intergenerational change, nurturing the soil with ash and nutrients released from the incinerated trees. Most of the dominant plants in Australia, especially eucalypts and acacias, at least tolerate fire, and in many instances actively promote it. They have, as Gammage would say, an alliance which has been beneficial to them over millennia.

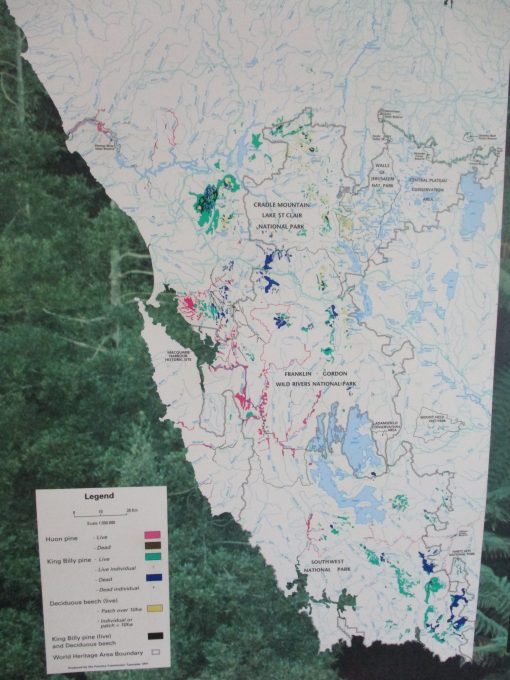

But the ancient wet temperate rainforest trees of western Tasmania are the losers in this fire alliance. Evolving before fire was more than an incidental part of the landscape, and well before humans arrived on the southern continent and joined the fire alliance, Huon and King Billy pines can withstand rain, flood, insects, nutrient-poor soils, low light, competition, cold temperatures and strong winds. But not fire. They are killed by the first sign of smoke and heat, and, in the case of Huon pine, the flammable oil that suffuses the timber, methyl eugenol, causes the wood to almost explode when burnt. There is no coming back from fire for these trees.

By the time Europeans arrived in Tasmania in the early 1800’s the Aboriginal clans had developed a remarkably sophisticated system of managing the country using small and carefully timed fires. Planned with surgical precision to promote feed for wallabies and other grazing animals but to leave intact the forests which supported ecosystems important to indigenous food, shelter and ritual, button grass plains punctuated forests, and tree-lined rivers protected water quality. Fires were rarely big enough to escape up the mountain slopes where King Billy pines stood sentinel, nor hot enough to penetrate into wet riverine rainforests where Huon pines were well defended by soggy soils and fire retarding neighbours.

By the late 1800s this security was challenged, as Europeans moved into the west coast, displacing the Aboriginal custodians and denying the regular maintenance fires that had kept ecosystems in healthy order. Whether by ignorance or accident, the new settlers saw fires develop in the hot and dangerous times of the year, which quickly became uncontrolled conflagrations. Several fires in the 1870’s and 80’s did damage, and then a huge fire in 1896 started near Queenstown and ripped across the western ranges, down through south western Tasmania, and only stopped when it reached the coast at Louisa Bay. Fire historians can see its effect on the landscape to this day. More big fires in the 1930s and 60s extended the damage even further, and travellers on the Lyell Highway can see the effects of the latest fire from 2016 on the eastern shores of Lake Burbury and up onto the Raglan Range.